By Raul Ilogon .

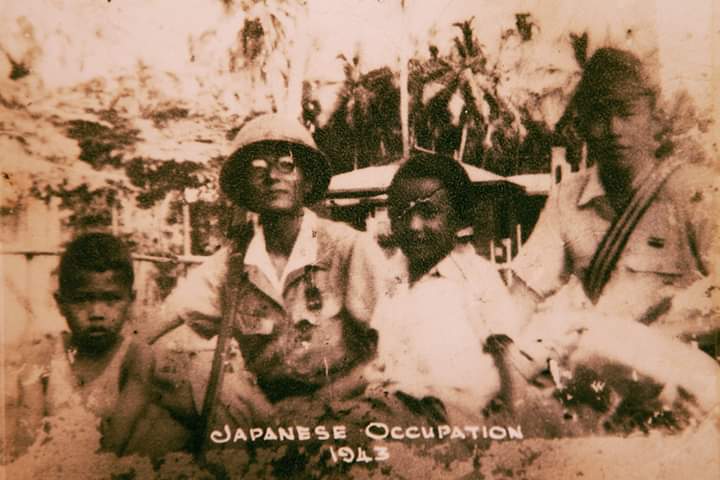

AS a child, I loved listening to my father’s stories about his World War II exploits as a young guerrilla civilian volunteer of WW2. Against all odds, they fought and endured the Japanese occupation. They risked their lives rather than live with bended knees.

It was an endless rewind told over lunch or dinner. Surprisingly, we nèver got bored of hearing the same story told over and over again. It was as if my siblings and I were hearing it for the first time.

My father’s war stories never failed to excite us. His eyes glittered as he retold the battlefield heroics of Maj. Angeles Limena and Maj. Fidencio

Laplap. Their bravery and defiance against the mighty Japanese army gave hope to the demoralized ànd defeated people. Their name became by-word and traveled far and wide across Mindanao. They were there when the people needed a hero. Their battles told them that the Japanese can be defeated. Their victories, however small, shattered the Japanese invincibility.

My father, Jesus B. Ilogon, was 16 when World War 2 broke out. He was 4th year high School at Misamis Oriental High School (now Mogchs).

After the April 8, 1941 flag ceremony, they were told to go home. Pearl Harbor was bombed. War had started. They were the last family in Licoan to evacuate to Lapad, Laguindingan. His mother was too weak to travel having suffered a miscarriage. Unfortunately, the aerial bombing that shook the ground was too much for his mother and the unborn baby to take.

One day the Japanese puppet mayor of Alubijid made a speech during the Tabo at Aromahon, a sitio near their evacuation place in Lapad, Laguindingan. He was ashamed of what he heard. The Japanese puppet mayor of Alubijid was peddling “fake news.”

Unable to contain his anger, he shouted at the top of his voice: “Bakak! Dakpa!” The mayor shouted an order to his policemen.

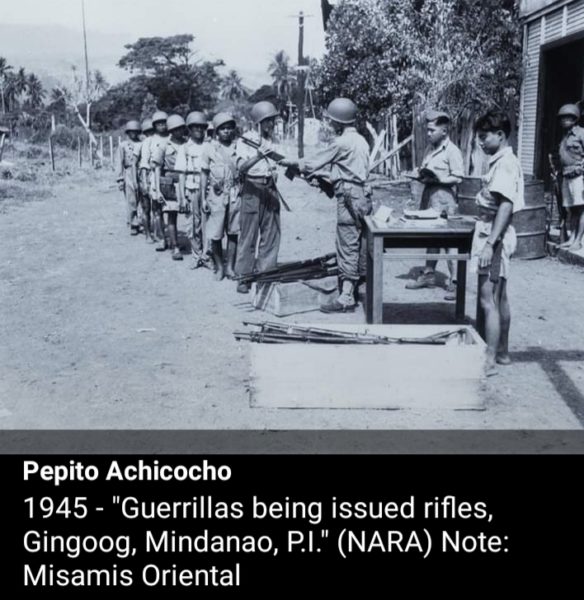

He ran home to Lapad as fast as he can. The excellent running skill saved his life and several times later when he joined the guerrilla movement. The guerrillas were issued only eight bullets. After firing four bullets, the guerrilla must run

as fast as he can.

The anguish was unbearable when he learned of the death of his basketball teammate. Before the war, they had a basketball team called Parke. Cox Banquerigo resided near Parke, now Gaston Park. He was beheaded inside Ateneo de Cagayan campus for passing information to the guerrillas. He was 16 years old. He felt the urge to join the fight for home and freedom but his parents were against it. He was still too young and besides the Japanese were too strong. Everything was uncertain. In fact, there was no news if the Americans would come to retake the country, his parents said. But he was determined, so he ran away from home and enlisted in Alubijid with the guerrilla group organized by Maj. Angeles Limena.

He was assigned in 120th Regiment, 108th Division with Regimental headquarters at Lugait Central School, Misamis Oriental.

Young as he was, with no military training, he started as a stable boy, tending horses of officers and enlisted Usaffe men. He was transferred to office duty when an officer discovered he knew how to use a typewriter. He also rolled local tobacco, called Tigol, for the officers.

His training on the guerrilla tactic of shot and run paid off when large Japanese troops attacked their headquarters at Lugait. They fought hard and pushed back the Japanese to Iligan.

In the troops’ formation after the Japanese withdrawal, the regimental commander acknowledged him as the only soldier in the whole regiment who fought the Japanese in two separate encounters in one day, while berating some officers and Usaffe veterans who ran and flee at the sight of the enemy.

“Bata, magaling ka!” His Ilocano Regimental commander, Maj. Pedro Andres, said in Tagalog, in front of the troops.

As his reputation grew, he was given an assignment fit for senior and veteran soldiers. First sergeants started giving him big responsibilities, bypassing senior and veteran soldiers.

“It felt awkward. I was only a private and very young,” he said.

The young and brave civilian volunteer became a choice bodyguard of officers on dangerous missions. But perilous missions paid off and rewarded with pleasures when Iligan was liberated.

Festive prominent Iliganon families invited officers to parties. As a trusted bodyguard, he was ordered to tagged along.

“For the first time in two years I tasted real food,” he said. “The host entertained us with piano music played by their lovely daughters who were teenagers like me. Some of them were my classmates at Misamis Oriental High School. But I avoided them and stayed at a safe distance because I do not want them to smell my body odor which was common to guerrillas. Besides, I was insecure – being barefooted.” He continued talking – smiling and feeling amused by the memory.

One of the highlights of his guerrilla life was the time they went to Jimenez, Misamis Occidental.

He was chosen as one of 12 escorts when Maj. Limena was ordered to report to the 10th Military District headquarters. The escorts were Pvt Abres, Pvt Enad, Pvt Abella, Pvt Ibonia, Sgt Goerge Carvajal, Sgt Delfin

Reyes, Pfc Boboy Austria, Pvt Quinton Joaquin, Pvt Mariano Francisco, Sgt Domingo Baldomino and Pvt Jesus Ilogon.

The officers with Maj Limena were Capt. Ricardo Abellanosa, Capt. Vicente Austria, Capt. Rolando Tiano and Lt. Ramon Legazpi.

The trip itself was dangerous. They had to sail across the Japanese-infested Panguil Bay to the headquarters of Col. Wendell Fertig, CO of 10th Military District. (to be continued)

Disclaimer

Mindanao Gold Star Daily holds the copyrights of all articles and photos in perpetuity. Any unauthorized reproduction in any platform, electronic and hardcopy, shall be liable for copyright infringement under the Intellectual Property Rights Law of the Philippines.